As July wilts the stems across Kansas fields, a low thunder off in the distance keeps every grower attentive. The conversation turns again—always it seems—to moisture and markets as farmers look toward harvest. Lance Rezac, a soybean producer from Pottawatomie County, listens to his rows for signals while eyeing the sky for errant clouds. Early planting this year—a gamble placed with one foot in spring mud and another in market speculation—has nudged Rezac’s expectations: an autumn hustle might kickstart earlier than usual.

Standing between optimism and pragmatism is where you’ll find most Kansas growers these days—Rezac included. As he says, “the soybean seems to know when the season is ending, and they seem to all ripen at the same time.” Each plant on his diversified operation rides its own biology even as weather patterns break historical habits; a farmer’s hope glints somewhere between that consistency and chaos.

Across Kansas’ fields, USDA’s June 2025 snapshot tells of mostly healthy soybeans: just 1% very poor, 5% poor, while over half are still rated good or excellent right before pod set. Only slightly behind last year’s schedule (with 86% planted compared to last year’s 91%), what matters most now isn’t more seed pressed into soil—it’s whether drought tips yield potential into wishful thinking or profitable reality.

“Throughout the entire growing season,” Rezac says, “producers of every crop are praying for timely rains to ensure that they will have high yields.” The refrain echoes through co-ops from Colby down to McPherson: rainfall remains the coin toss upon which so many inputs hinge.

Parched topsoil sometimes presents new riddles; USDA fieldwork reports mention around 5% of Kansas land as “very short” on moisture with only 7% showing any surplus lately. These quirky imbalances can mean some patches thrive while others seem spellbound by drought’s patience.

But fate doesn’t arrive on raindrops alone—the critical role of trade sits squarely beside weather patterns when it comes time for combines to roll. With Lance Rezac formerly serving as chairman for the US Soybean Export Council (USSEC), very few appreciate how global news seeps straight into rural ledgers more than he does. If trade pacts falter or tariffs return like moths seeking light bulbs during late-summer evenings, then even bumper bins could squeeze profits thin enough your average coffee shop philosopher would call it bean-counting folly.

American soybeans nestle deeply within international supply chains—not just preferred protein abroad but pivotal feedstock found everywhere from Japanese tofu factories scrambling eggs with dashi broth all through Vietnamese aquaculture systems fattening catfish downstream from Vinh Long. For each cargo ship waiting upriver at New Orleans or bobbing among Asian portsides lies someone back home hoping shipment schedules hold true—and that political crosscurrents don’t sever those lifelines.

A swift decline in export opportunity can turn optimism brittle almost overnight—for many years China has been either firebrand customer or cautious observer depending on diplomatic moodswings rarely synchronized with North American rainfall calendars.

Kansas itself stands out not only due its maiden crop condition ratings but also because grower associations here push aggressively toward ensuring resilient deals overseas; lobbying efforts dovetail awkwardly yet persistently into daily life on these farms—navigated phone calls about fungicide timing often interrupted by update alerts concerning pending South American contracts.

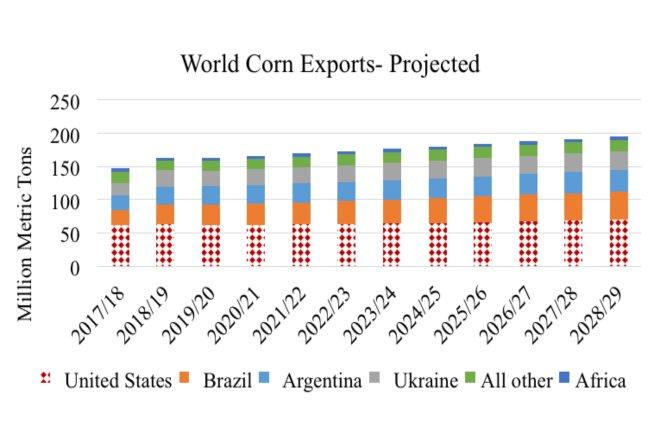

Letting your mind wander across fallow quarters reveals how volatility elsewhere reverberates domestically: slowed vessel traffic along Gulf routes because Argentina upped output suddenly means grain elevators hum different tunes come October afternoons—even if rains broke evenly here in June.

These unpredictable linkages breed behaviors unique inside agricultural circles—a kaleidoscope where economic indices flicker like wheat heads under inconsistent sunshine.

Kansas farmers don’t keep their eyes glued exclusively onto sky nor spreadsheet columns—they learn stubborn pragmatism shaped by both climate and commerce.

Some seasons surprise anyway: late beans outpacing early guesses due persistent subsoil reserves; rumors swirl at cafés about Brazilian plantings sprinting past projections (yet half their promised rain never materializes). Nothing peels away preconceived notions quicker than an unexpected frost quirkily sidestepping one county yet kneecapping another nearby mile marker westward—even radio hosts adapt scripts mid-broadcast around such shifts without apology required.

Trade fats add flavor beneath headlines few residents outside farming communities fully digest until supermarket prices swing months later—the butterfly effect gets grounded reality each harvest cycle in places like Salina whenever foreign inspectors tour local handling plants incognito sporting nondescript ballcaps.

On any given September dusk you’ll find Lance Rezac walking rows bathed gold against weathered fences wondering aloud whether next season brings relief or more trial—with ears always tuned both above for thunderclaps and abroad listening intently for muted shuffles among diplomats well beyond Flint Hills horizons.

Certain truths remain unhurried through modernity’s parade: rainfall talks loudest early summer but treaties whisper fortunes long after trucks bed down outside processing silos before first frost bites stubborn green stems flat against broken ground. Two items always worth double-checking again before sleep settles heavy—field moisture…export stats embedded somewhere upwind from tomorrow morning’s sunrise.