From Seeds to Global Harvest: A First-Generation Indiana Farmer’s Soybean Empire

Anyone passing through the hamstrings of west central Indiana in mid-July will spot vast blankets of emerald green, all rows leading somewhere dusted with hope. The air hangs heavy—not only from humidity but also with possibility, a feeling familiar to those who have risked so much on a handful of seeds and favorable weather. That was true for Elizabeth Hardy, a first-generation soybean grower whose acreage quietly transformed into something that people around the world now talk about over trade calls and shipping manifests.

Elizabeth wasn’t born into agriculture; her family worked paper mills along the Wabash River. Her decision to plant soybeans startled more than one neighbor, causing murmurs at auction barns where folks purchase everything from plowshares to solutions for removing ditch grass.

Launching any farm is no gentle slide into prosperity in these parts—instead it’s an ascent up gravel-strewn hills smoothed by decades of calloused hands before you. Yet Hardy approached her debut fields not with romantic notions but longer calculations—soil composition percentages scribbled onto greasy napkins during dinner at single-stop towns.

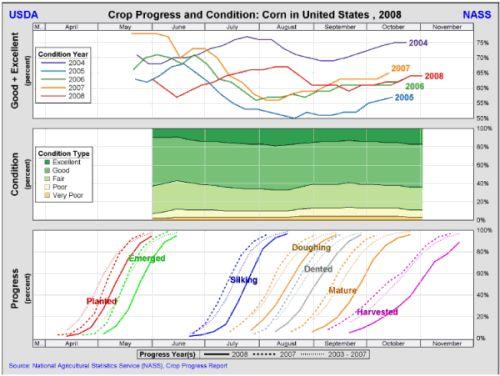

Some seasons start slow, others can’t wait—the 2025 season began amid stubbornly cool nights that set back early emergence across much of southern Indiana. Elizabeth wandered soft paddocks looking for black cutworm evidence while balancing commodity price hedges on her phone—a practice oddly normal among younger growers now tuned as much to markets as moon cycles.

Projections in Indiana changed gears this year; wheat lost some territory while corn nudged upward by 200,000 acres—meanwhile, soybeans shrank slightly by 100,000 acres though they remain ahead overall at about 5.7 million planted. This convergence isn’t random statistical noise—it reflects signals interpreted locally: global market currents clashing against Midwest pragmatism. For Hardy and neighbors alike such shifts define what gets planted and what sits quietly in bins waiting on improved basis or perhaps just patience rewarded later.

Farm profitability isn’t fixed like concrete; instead it reshapes itself whenever input costs bob or government programs intervene unexpectedly—as they did this spring when net farm income projections shot up roughly 40% across Indiana due largely to changing federal payments. This windfall cycled through rural banks and local co-ops simultaneously igniting optimism one morning while fueling debates about reliance on subsidies once the sun fell behind machine sheds that evening.

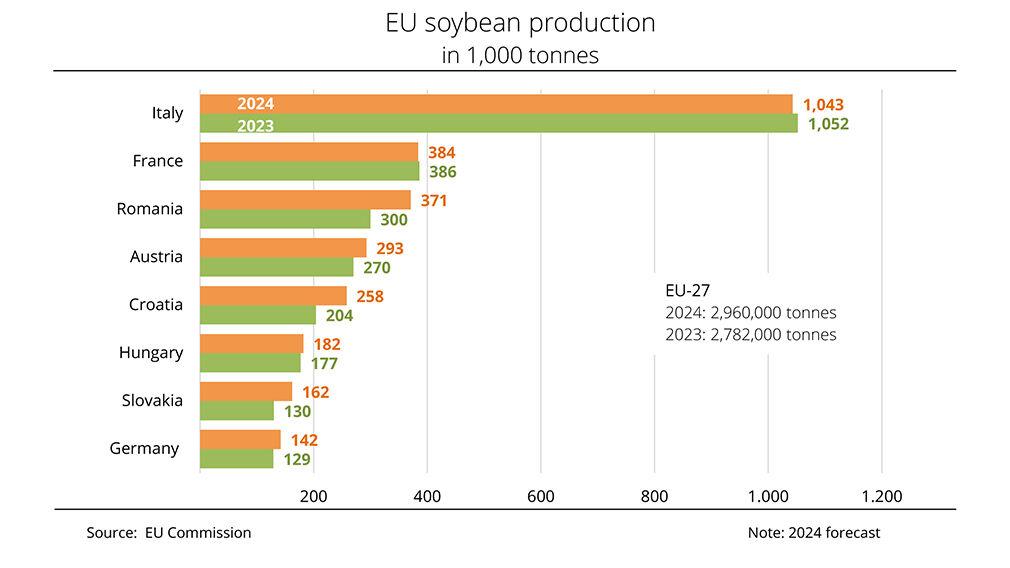

A soybean “empire,” especially built within twenty years out here where generations predate highways themselves? There’s never truly an emperor behind these green expanses—more often it’s managers who treat logistics software like lucky dice rolls paired alongside well-timed prayers for August rainclouds. In Elizabeth’s operation today every acre feeds contracts stretching further than state borders: Brazil buys specialty protein isolates; Japan requests non-GMO export runs destined for tofu found nowhere near Terre Haute diners.

The field stories are sometimes interrupted—a misplaced tool caked under tire treads might spark a week spent reorganizing outbuildings rather than managing trade emails—but somehow things progress toward combining time nonetheless. It wouldn’t be inaccurate to describe this movement as dictating one’s dance steps via satellite navigation—yet occasionally skipping music altogether because there’s hail predicted just northward above Greencastle tonight.

Many anticipate global arcs but live rooted here among rare wild cucumbers tangled near tile lines installed generations earlier by German immigrants seeking stonier fortunes elsewhere; other concerns press nearer such as dicamba drift threatening clean seed lots two farms south during wind-whipped springs nobody welcomes anymore except insurance agents whose calendars seem permanently booked until September FEMA reviews arrive (if they do).

With second shucked meaning given even familiar phrases—a “good stand” might measure less strictly plants per acre nowadays than resilience whenever input timing goes haywire due human error or distributive delay from inland terminals underwater again after March flood events canceled barge shipments yet another year. Weather risks blended with national market swings keep profit projections moving like spotted calves forgetting which fence belongs to whom after dark thunderstorms pass overhead without pause.

It doesn’t seem odd here if record yields someday coincide with news anchors announcing swift decline in Chinese soy imports due regulatory change—or if midnight freight convoys trundle east hauling beans toward ports unlikely known by anyone who hasn’t memorized FGIS grading tables (or maybe collects rare ag company hats from obscure Minnesota suppliers).

Not far back Elizabeth pondered switching split-row planters entirely over into regenerative cultivars designed less for record-breaking bushels per acre metrics—and more defined instead by carbon drawdown tallies required ex post facto via grant applications filed late over slow winter dialups still common enough if you drive far off state route two-fifty-one some evenings past turkey barns lit up red warning lights beneath Orion constellations barely visible between new cell towers blinking methodic blue atop old railway sidings.

To say ground is merely tilled here misses layers grown thick as old fenceposts half-swallowed beside misaligned field edges bulldozed long ago when someone said progress meant straight lines above all else—the tale stays richer amongst those willing sometimes letting ideas scatter sideways then settle gently wherever idle combines rest over hard-won autumn harvests yet unresolved whether luck or persistence irrigates future fortunes best woven quietly seed-to-shipment each unpredictable season again henceforward.